Chapter 1 - Secrets of the Snake Charmer

“The mind is primed to react emotionally to the sight of snakes, not just to fear them but to be aroused and absorbed in their details, to weave stories about them.” Edward O. Wilson, 1984

On a dark, early morning in a small east African village in southern Tanganyika, a green mamba was stalking a lizard in the upper branches of a large mango tree. Hunger stimulated the snake to hunt after shedding its skin. The lizard escaped, but the snake continued its search for food. The foraging mamba crawled down a branch onto the thatched roof of a hut where nine people slept. The six-foot long snake burrowed its way through the thatching until it lost its hold on the dry leaves and fell onto a sleeping member of the family. Exactly what happened next is unclear but the following seems likely. One of the family members, partially awake may have brushed the snake or grabbed it. The snake, fearing for its life retaliated and struck the human. In the dim light, the snake was barely visible, but other members of the family awoke and subsequently tried to rid themselves of the unwanted reptile but were instead bitten. Screams from the hut awoke other members of the village, some of the men believed they were under attack, grabbed weapons and emerged from their dwellings swinging large knives at their neighbors who were also confused and running around in the darkness. Eventually, order took hold, and the villagers gathered outside the mud-dwelling where the screams had started. They dared not enter the hut but eventually, a man emerged holding his throat before he crashed to the ground. The village shaman examined the body and diagnosed the cause of death as due to the bite of a mamba. At first light, the hut was entered, and the bodies of two men, three women, and two young children were lying in contorted positions. Eight were dead; the only survivor was a baby.

This story opens Alan Wykes’ book Snake Man, The Story of C. J. P. Ionides. According to Wykes, the village headman summoned Ionides, an East African snake catcher, and game warden. Ionides arriving at the village, quickly located, captured, and removed the snake from the village.

Four years after Wykes’ book appeared Ionides’ autobiography, Mambas, and Man-Eaters, was published. Ionides recounted a story reported having occurred in South Africa, where a black mamba dropped out of a grass roof onto a sleeping family. The snake was said to have killed five people. But all of this supposedly happened before Ionides birth and Wykes, therefore, used considerable artistic license in crafting his story. Clearly, Edward Wilson’s statement is supported; the human mind is fascinated with snakes and obsessed with crafting snake stories.

Evolution has produced a rich diversity of life forms on planet Earth. Among these are primates (humans, apes, monkeys and their relatives) and snakes; two groups of vertebrate animals that have unique and specialized adaptations, as well as a long and complex history of co-evolution on the African continent.

Primates are large-brained, visually oriented mammals that are highly social, communicating and interacting with each other in complex ways. Primates have forward-facing eyes with lids that close when they sleep, and when awake they appear alert. Primates use parental care to help their genes succeed in the next generation, but much is learned during development and growth and is used to survive well-passed reproductive age. Primates are mostly plant-eaters, rarely are they carnivorous. They forage for food, using fingers guided by their eyes to collect and place small pieces of food in their mouths, and grind it into yet smaller pieces while lubricating it with saliva. Food is frequently needed to maintain the high-energy requirements of the brain and other organs, as well as to maintain that constant body temperature needed by all mammals.

Snakes are small-brained, limbless-reptiles that depend upon vision to varying degrees, but for much of their information they rely heavily upon molecules picked up on the surface of their tongues and analyzed with their brain. This chemical information is particularly important in the recognition of food and locating mates. Snakes lack facial expressions and eyelids; their eyes are always open even when they sleep. Snakes, like all reptiles, differ from mammals in using external sources of heat to warm their bodies. Therefore, snakes need only a fraction of the calories from food required of a mammal of the same weight. Additionally, snakes are non-social, and parental-care is limited, and while some of the behavior needed for survival is learned some is biological in origin. Snakes swallow whole animals and have evolved mobile skull bones and elastic organs that allow their bodies to accommodate large prey. They lack the ability to bite off easily digested small pieces of large prey for easy digestion; instead, they saturate their prey with hydrochloric acid and enzymes that liquefy the food for digestion. Some species take prey that is equal to or greater than their weight and some larger snakes are capable of eating primates, and even humans are not entirely safe from being consumed by the largest of snakes. Snakes have evolved venoms made and stored in glands around the mouth for injection into prey through fangs or delivered into puncture wounds. Venom subdues the prey, renders it harmless, and may start digestion before swallowing the prey. Not surprisingly, venom may also be used for defense when the snake encounters a potential predator. If Wilson is correct about the human brain being primed to react to snakes, other primates might be expected show the same trait.

This author foolishly accepted an unwanted baby squirrel monkey. Caged in a classroom laboratory with numerous snakes and lizards. When a snake came within view the monkey’s reaction was vigorous and attention-getting, it screamed while racing back and forth in its cage and launched its body against the walls. The response was so emotional we covered the monkey’s cage whenever a snake was in its line of sight. The monkey soon began to show the same reaction to anything snake-like in shape; rope, water-hoses, and electrical cords elicited similar behavior. I suspect this was the result of the monkey’s realization that live snakes were indeed living in its environment. But, how did this young monkey, presumably born and raised in the isolation of captivity and naïve to snakes, know that snakes were potentially dangerous? Are all primate brains programmed to react to snakes?

Fear of snakes had, and to a degree still does have, survival value for humans and other primates. Venom injection can rapidly lead to death or severe injury and merely avoiding snakes can be advantageous to any primate. So, if human brains are programmed to fear snakes why are we simultaneously fascinated by them? And, why do we love to obsess about snake stories?

Did Snakes Help Shape Primate Brains?

Widespread fascination, dislike, and fear of snakes and their presence in myths, folklore, and art reflect millions of years of snake–primate co-evolution. Yale astronomer, astrochemist, and exobiologist Carl Sagan hypothesized that mammalian brains may have become sensitized to snakes and other dangerous reptiles even earlier than the origin of primates in mammalian evolution. Human behavioral studies have demonstrated brains are predisposed to fear snakes and quickly become sensitized to snakes from watching the response of others. Using visuals of snakes and measuring physiological responses of sweating palms and heart rate the response to snakes was more intense and lasted longer than visuals of guns paired with a loud noise. These studies suggest fear of snakes was more likely due to evolutionary history rather than cultural conditioning.

Lynne Isbell, an anthropologist at the University of California-Davis, expanded this hypothesis to help explain the fear, fascination, and emotional reaction of many primates to snakes, as well as human interest in them. The hypothesis draws on evidence from a variety of sources and proposes that the brains of Old World Monkeys (and to a lesser degree New World monkeys), apes, and humans have been partially shaped by snakes, particularly venomous snakes. Isbell suggests forward-facing eyes, close-up vision, reaching for an object guided by eyes, and the expansion of pathways for color and object recognition in the brain are the result of primates and snakes living and evolving together. Her arguments and evidence are compelling.

Visually recognizing snakes at a distance can be a life-saving ability for a primate. Isbell proposes that brain centers associated with vigilance, learning, and memory tend to be conservative in most groups of mammals, but these areas have expanded and are strongly linked to visual systems and fear centers in primates.

Madagascar is home to lemurs (primates) that have not developed these areas of the brain and the connections between them because they have not had to co-exist with venomous snakes. Dangerously venomous snakes are absent from Madagascar, but there are large booid snakes capable of constricting and consuming lemurs. Eastern Hemisphere primates (with the exception of those lemurs on Madagascar) have had a continuous history of living with both large constrictors and venomous snakes. Since primates first evolved, (probably prior to the Paleocene about 60–80 MYA) primate predators such as large raptors and carnivorous mammals had not yet evolved. Isbell considers the following scenario.

The Cretaceous primate ancestor was small, nocturnal, and reached for and grasped food items such as fruit, flowers (for nectar), and bugs based upon the odor, similar to rodent behavior today. The primate ancestor also had its eyes located on the sides of its head, so there was little overlap in the visual fields and non-visual control of reaching and grasping. Predation by constricting snakes was a major factor in selecting that individuals survived and reproduced. Cretaceous constrictors selected the ancestral primates for eyes that were more forward, more mobile, and capable of focusing on close objects with some depth perception. At this time, the fear module expanded with the ability to detect snakes. Increased dietary sugar from nectar provided more calories for the expansion of the energy demanding brain improving its ability to respond to the motion, sound, color, and form, as well as allowing it to be more alert and attentive to its surroundings. By the Paleocene, (65–54 MYA) snakes with efficient venom delivery systems were present, no longer were primates just in danger of being eaten by constrictors. Strikes from venomous snakes could result in a primate being eaten, but a defensive strike from a small venomous snake meant serious injury or death even though the primate was too large for the snake to eat. Venomous snakes selected primates for an expanded fear module in the brain, the eyes were now even closer together, greatly enhancing close-up vision and depth perception. The glucose intake increased again when the early primate shifted its foraging behavior to daylight, relying more on vision than odor for finding food. Early anthropoids were present in the Eocene (54–34 MYA), and these would eventually evolve into the modern apes. By the Oligocene, (34–23 MYA) more modern primates relied less on odor and more on vision; expanded the brain's fear module; the eyes were now facing forward for improved close-up vision and depth perception, and color vision now involved three color receptors on the retina of the eye. The actions of reaching, grasping, and leaping were now uncoupled from the evolution of binocular color vision. Other small and medium-sized mammals took a different evolutionary tact to deal with venomous snakes; they evolved venom-neutralizing molecules that circulated in their blood.

We take the simple act of reaching out to pick up a piece of food for granted but imagine a distant ancestor, with less ability to see objects close-up, reaching for a berry or bug and being struck by a snake not seen. The snake was motionless, and its color and pattern blended with the surroundings, invisible to the early primate.

Today, snakes still avoid detection because of their cryptic coloration and patterns. I have the vivid memory of rolling a log in an east Texas forest in an attempt to locate snakes. No snakes were visible as I reached down and lifted the log. But as the log was lowered motion near my left boot attracted attention, a copperhead underfoot was chewing on the toe of my boot. The copperhead was invisible in the leaf litter of the forest floor; only the motion of its trapped body attracted my attention.

After 86 million years of snakes and primates living together, snakes generate the intense, visceral reaction monkeys, apes, and humans feel at the sight of snakes. But, it also provided a platform for further primate evolution, visual social communication that has become so important in human development. Co-evolution of snakes and primates also provides a basis for understanding human fascination with snakes, their roles in mythologies, and their symbolic positions, which are often conflicting and contradictory, in cultures the world over. And, why no matter where you travel from Iceland to Thailand people have snake stories to tell, even though snakes may not be present in their modern environment.

Snakes and the Pre-Scientific Mind

Several biological attributes of snakes have helped create the illusion that snakes are more than simple animals. Snakes can appear and disappear quickly. Snakes are also displaced during flooding and becoming more obvious to the casual observer as they are washed out of burrows and seek higher ground. Therefore, the association between snakes, floods, and crops are not difficult connections to make.

Shedding a complete skin as they grow may have given rise to the idea that snakes are reborn and therefore immortal. Male snakes (and lizards) have a divided penis providing them with two organs for mating, and copulation may last hours to days. Females of some species may give birth to 100 or more young (or lay a similar number of eggs). And, both sexes are penis-shaped. All of these traits would suggest longevity and fertility to the pre-scientific mind.

Venom provides snakes with the power of death with a minimal amount physical trauma, death from snake bite would certainly seem magical to ancient peoples. While some snakes deliver venom that acts primarily on nerves and muscles, other snakes have venom that acts mostly on the circulatory system and causes massive, spontaneous bleeding from body openings, and some species have combinations of neurotoxins and hemotoxins.

It is likely that spontaneous bleeding has linked snakes and menstruation in pre-scientific cultures around the world. In Lebanon rural people believe the shadow of a menstruating woman immobilizes snakes and kills plants; some Australian tribes exclude menstruating women from waterholes because the guarding rainbow serpent may kill her and abandoned guarding the water resource; a menstruating women in an Argentinean tribe can kill a snake by stepping over it; in Bolivia a girl at first menstruation in sequestered in a hammock for 90 days while older women beat the paths to the hut to kill the snake that bit her; North African and Middle Eastern Semitic peoples explain menstruation as a supernatural wound from snakebite; in Italy and Greece rural people warn their menstruating daughters not to wander in vineyards because they will attract snakes. The list goes on.

The evil reputation given to snakes in Judeo-Christian cultures can be traced to the Bible’s book of Genesis and the snake tempting Eve to eat an apple from the tree of knowledge, the fruit forbidden by god. Anthropologists who study myths see this as an “origin of death story.” The Biblical story is, in fact, a version of a much more ancient story that can be traced to the Sumerians at least 5000 YBP and similar stories can be found in tribal cultures across the planet. Near Mt. Kilimanjaro the Wapare people believe a snake tempted a man to eat forbidden eggs and he was punished by having his tribe reduced to two people, a male, and female, the founders of the current population. The Wafipa and Wabende peoples living on the edge of Lake Tanganyika believe that the god Lenza asked who wanted to die while all the animals were sleeping. The snake had anticipated the visit and said he never wished to die.

Snakes and snake imagery are ubiquitous in creation and origin of death stories the world over because snakes are widely recognized as immortal, the source of fertility, and messengers of death, a role they have most likely filled since the origin of modern humans.

Snake Charmers

Two men carrying bags and baskets and accompanied by a macaque were walking along the roadside in southern Sri Lanka when the driver of our van haled them. Within minutes they opened their containers to reveal two common cobras and an Indian python. One man sat on the ground and played the flute in front of a basket, soon two large cobras ascended from the opening. Swaying with the movements and instrument of the snake charmer the snakes appeared to dance, and therefore appeared to be under the control of the flute-player. The other man displayed the python around his shoulders and taunted us to touch it, not knowing that he was daring several herpetologists, who also kept pythons for pets. After a short performance and a photography session, they demanded the equivalent of US $100 for the show but received something less. Exactly what was their performance about, were they simply hustling tourists with cheap entertainment, or was there some other meaning?

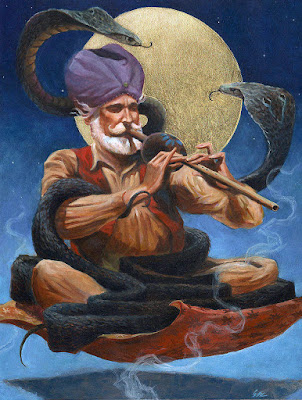

Snake charmers are best known from Africa and South Asia, where images of the traditional flute-playing snake charmers sitting in front of baskets are common [Figure 1–1]. However, snake charmers occur across time, geography, and cultures, often charming more than snakes. Frequently they develop a following with beliefs that the charmers hold secrets, secrets that allow them to control snake behavior, overcome the effects of snake venom, and resurrect those who have died from snakebite. On one level the control of snakes may be best understood as an icon for the control of nature, a dominant theme in cultures worldwide. Consider the following examples.

In North Africa, the Psylli, were the displaced remnants of ancient Libyan tribe that lived on the Gulf of Sidra. Conquered by the nomadic Nasamones, the Psylli became a well-known snake-charming sect that controlled an international trade in poisons and antidotes in ancient times. They tested the paternity of the children born into their clan by exposing infants to dangerous serpents. If the child was fathered by one of them it was unharmed; an alternative test was to place the child’s clothes next to snake, and the snake would become numb, for their body odor was believed to anesthetize serpents. Psylli saliva was believed to be toxic to snakes, and they were said to be immune to the bite of venomous snakes. During the reign of the Pharos they would chant incantations to the Egyptian sun god Ra during their performances; during the 12th century they were converted to Islam, and the incantations came from the Koran. They danced for departing caravans journeying to Mecca and their performance included biting, tearing, and eating the flesh of live snakes; contorting their faces; foaming at the mouth, and partially swallowing snakes to absorb their powers. The Psylii cured snakebite by touching the wound with their fingers, spitting on the wound, or lying naked on top of the victim to neutralize the venom. They were paid to remove snakes from houses and were hired to follow Roman armies through snake-infested areas. Augustus Caesar had a Psylli attempt, unsuccessfully, to save Cleopatra from her suicidal snake bite. However, Roman physician Claudius Galenus (Galen) considered execution by snake bite a humane practice in Alexandria, but there is little evidence that snake bite or snake venom played a significant role as homicidal procedures in ancient Rome. In Italy, the Marsi were the snake charming counterparts of the North African Psylli. The Marsi or “traveling people” were a marginalized society inhabiting the central mountains of Italy; they had the reputation of being uncivilized, warlike, and having unusual religious practices. They lived in poverty but made excellent soldiers in the Roman army, and are best known for their skills as snake hunters and snake charmers as well as druggists. They visited cities to sell poisons and drugs, and to profit from their snake charming performances. Like the Psylli they had the reputation for being immune to snake venom, and Galen consulted them on drugs and antidotes.

In Europe and the Middle East, snakes are closely associated with health and fertility. Symbolic snakes coiled around a staff date to at least 5000 YBP in the Sumerian culture where they symbolize the fertility god Ningizzida. Moses and Aaron were snake shamans of the ancient Israelis and led their followers out of Egypt under the symbol of a bronze serpent on a pole, the Neehustan. Gazing at the sculpture was said to cure snake bite and therefore restore health. In Rome, Aesculapius became the god of medicine, his name derived from the Greek askálabos, meaning serpent. Homer, the blind poet of ancient Greece, considered Asclepius a prince of Thessaly before being recognized as a god of medicine and developing a cult of followers. The Romans co-opted Asclepius and his cult and he became known as Aesculapius. Aesculapius’ staff became the symbol of healing and longevity. Roman troops carried poles with snakes tied to them into battle and used the same as a flag for a truce.

Snakes in trees, snakes wrapped around poles, singly or in pairs is an ancient symbol that has been modified by many cultures. The caduceus, intertwined serpents on a winged staff, was adopted as a symbol for the United States Army Medical Corps in 1902; previously the Corps used a cross. Today, a stylized, loosely coiled snake around a pole remains the symbol of the American Medical Society.

The Druids of the British Isles used snakes in their ceremonies and sacrificed them in a Midsummer’s Eve fire festival as recently as 1900. Frazer described the festival at Luchon in the Pyrenees that involved burning a 60-foot column of brush and dumping live snakes into the column above the flames. The snakes climbed to the top before they fell into the fire.

In Asia, snakes are widely considered guardians of wealth and symbols for fertility. A snake priestess leans over a hooded king cobra in Myanmar and kisses the top of its hood; this is believed to encourage the monsoon rains and the success of crops. In Cambodia and Thailand Buddha is frequently illustrated seated on the coils of a large cobra, while the snake’s spread hood covers his head like a protective umbrella.

In present-day Thailand, commercial snake charming occurs several times each day in the village of Ban Khok Sa-Nga, in Khon Kaen Province. In 1951 Ken Dongla was looking for ways to market herbal medicine and realized a snake show would gather a crowd where he could sell his herbs. He developed "snake boxing," a 10-minute event where he demonstrated his mastery over the king cobra [Figure 1–2]. He shared his cobra handling skills with other members of the village and today Ban Khok Sa-Nga is known as King Cobra Village, a major tourist attraction. Buses roll in with the curious throughout the day, and the visitors pay 10 baht to watch the show and be offered a variety of merchandise. The villagers consider this an opportunity to educate the public about the importance of snakes and nature. Snakes are kept by most if not all of the village households, some cobras as well as Burmese pythons, and village children are raised with snakes and participate in the snake show. While snake priests and priestesses have used the king cobra as a source of power and way to convince their followers of their ability to control nature for thousands of years, this Thai village has turned snake charming into a strictly commercial venture.

India is home to numerous tribal cultures that use snakes and snake charmers to control nature and the destinies of their peoples. The scattered villages and diverse cultures involved in charming India’s snakes suggests snake cults were once more widespread than they are today. Snakes, particularly cobras, are powerful fertility symbols in Indian folklore and Nág Panchami is celebrated at the time of the annual monsoon rains. Cobras are captured for use in religious rites that involve dancing through the streets and offerings of rice, milk, and honey, followed by the release of snakes in front of houses so that the people living there will receive the snake’s blessings. The blessings are usually directed at unmarried women who want husbands and married women desiring children. Rivett-Carnac observed Nág Panchami in 19th-century Nagapur and wrote, "Rough pictures of snakes in all sorts of shapes and positions are sold and distributed, something after the manner of valentines.... In the ones I have seen in days gone by the positions of the women with the snakes were of the most indecent description and left no doubt that, so far as the idea represented in these sketches was concerned, the cobra was regarded as the phallus."

Entire Asian societies have been built around snake charming. But, in the last two decades, the Indian government has attempted to prevent snake charmers from collecting snakes and staging performances in an attempt to conserve snakes. The charmers have retaliated with protests, threats to release snakes into government buildings, and have now formed a union and hired lobbyists. In the eastern Indian village of Padmakesharpur, in Orissa, more than 500 families, introduce their children to snakes at an early age. Marriages occur only between members of the village, and the men earn a living as snake charmers while the women work as tattoo artists. In West Bengal’s Bedia community about 20,000 snake charmers are imprisoned for defying the ban. The nomadic Bedia consider snake charming their right and the ban has economically impacted about 100,000 families in the Cooch Behar, Murshidabad, and Malda districts of West Bengal. The snake charmer’s union is now asking the government to establish snake farms so the Bedia can use their skills to collect venom. Thousands of Bedia paraded through the streets of Calcutta on February 17, 2009, playing their flutes without snakes in protest.

Snakes play multiple roles in Australian aborigines’ belief systems, but this has not stopped them from using snakes as food and developing herbal remedies for their bites. When a clan member is bitten by a snake, the shaman sings to drive out the evil spirits that entered the victim’s body during the bite. The mythical rainbow snakes of the aborigines guard precious water holes in otherwise dry environments, and they are involved in creation myths, as well as forming the laws and customs of many tribes. Because snakes form an important food source and guard water they are regarded as both life-giving and fertility symbols.

In western North America, the Hopi perform an August snake dance with live Great Basin rattlesnakes as well as local non-venomous snakes. The ceremony is a prayer for rain and snakes play the role of messengers that deliver the prayer to the spirits. Snake ceremonies were also practiced by the Mimbres culture of southern New Mexico, ceramic plates that depict serpent storm-gods date to 1000 YBP. The Mimbres used snakes in a late summer snake dance as well as in the Snake Society Initiation Ceremony. In northeastern North America, the Algonquians practiced the yuneha, a snake dance that represented a snake-shaped constellation, and they believed that the road to the afterlife was a bridge made from a giant serpent that could be crossed only by the faithful. Today, Appalachian Christian religious sects handle live timber rattlesnakes, cottonmouths, and copperheads to demonstrate their belief that god will protect them from venom if they truly believe. Modern America commerce has invented the unique rattlesnake round-up, local festivals that result in the collection of tens of thousands of snakes to promote local economies in rural areas and, at the same time, keep the world safe for humans and livestock. The Animal Planet channel has given five minutes of fame to numerous rattlesnake wranglers in a variety of programs that show adult men harassing wildlife.

America had a well-known snake charmer in the 1930’s and ‘40s, Grace Olive Wiley. Ms Wiley frequently gained media attention for her ability to handle rattlesnakes and cobras, but her interest in snakes was non-religious, instead, she promoted scientific interest in snakes, and her message was one of snake tolerance and conservation. The message that snakes are ecologically important and represent an interesting lineage of reptiles that should be respected and protected is very similar to that of television snake handlers today.

In South America, the Chibcha of Colombia have a serpent creator named Chiminigagua that lives in a lake, the Peruvian Inca’s had a serpent fertility goddess, and the Guarani of Paraguay have a guardian for nature that is a snake-parrot chimera. The Humahuaca valley people of northern Argentina parade a super-sized model coral snake in a cage through the streets during a festival to invoke the spirits of the earth. Snakes are pervasive in Mayan art and their role in that culture was undoubtedly important, albeit poorly understood.

A survey of snake deities found them missing only from North America Indian and Chinese cultures, and yet even within these societies snake symbols and stories are prevalent, with shamans and medical practitioners of both areas using snakes and snake as symbols. The abundance of snake emblems and symbols suggest the human obsession with serpents is ancient. Snake symbols wind their way through the universe on shards of prehistoric pottery, rock walls, and are associated with the figurines and images of fertility goddesses of cultures ancient and modern. Professor Wilson’s proposal that the human mind is primed to react emotionally to snakes is difficult to deny.

Secrets

How do snake charmers and snake handlers escape the wrath of the snake? How do they handle dangerous snakes with apparent impunity to venom, cure those who have been bitten, and control snake behavior? Buckland summed up what many others had undoubtedly suspected. “There is a reason to suppose that in both hemispheres those who handle these venomous reptiles have found some means of rendering them innocuous. What this means has yet to be discovered; but probably in some cases, it consists of anointing the body with some preparation distasteful to snakes.”

Speculation about how Hopi Indian snake dancers avoided the consequences of rattlesnake bites ranged from drugging the snakes, painting the dancers’ bodies with repugnant substances, consuming a potent drink that rendered the dancers immune to the venom, stroking the snakes before the dance to paralyze them, and simply removing the fangs.

In his Natural History, written about 2000 years ago, Pliny listed 196 ways plants could be used to prevent and treat snakebite. Subsequent authors, both ancient and recent have added to these, and the literature on this topic is encyclopedic in volume. Frequently the plants chosen for these treatments have some characteristic that links the plant with the snake in the human mind. Its seeds may make a sound like a rattlesnake when blowing in the wind, someone discovered a cobra in branches of a specific species of shrub, the stem coloration may have been similar to that of a mamba, or the plant may have been used for cures of other diseases with symptoms similar to those observed after a snake bite. Plant materials with strong odor or taste are popular treatments, tobacco (smoked, chewed or given in an enema), onions, garlic, and echinacea (extracted from the root of the coneflower) were used for preventing and treating rattlesnake bites. In his early 18th century book The Chinese Empire Navarette, a Spanish Dominican missionary believed Asian snake charmers were anointed with protective herbal juices. The Tamil of Sri Lanka ate the nux vomica bean, and Arabs used a drink made from the plant known today as the climbing birthwort for snakebite protection. Harvard herpetologist Arthur Loveridge asked an African fisherman what he did for bites from the water cobra, the man replied that the victim must remain in the water until a waterweed is brought to him for an antidote, should he leave the water he would not survive. Newman reported the African belief that a person bitten by a mamba must lie down on the cut branch of a tree with many leaves, while a shaman is summoned. The mamba, apparently obsessed with numbers, stays at the location of the bite to count the leaves on the tree branch, a process that can take up to two days. If the shaman arrives and provides 'muti' (medicine) before the mamba has completed its counting the victim will live if the mamba finishes counting before the shaman arrives the victim will die. Newman suggested that this is a remedy to protect the shaman, for who can say when the mamba finishes counting?

Not surprisingly, alcoholic beverages have been suggested as a snakebite remedy and preventative on every continent; and vegetable oil, particularly olive oil, was used as a snakebite cure at least 800 years ago. Opiates were also used, and it was believed that they neutralized venom. Other snakebite remedies included vinegar, turpentine, iodine, potassium permanganate, salt, gunpowder, ammonia, and a range of inorganic salts. Some of these were very popular treatments that were swallowed, injected, or rubbed into cuts.

Animals and animal products were also involved in folk remedies, one of my favorites was the split-chicken recipe that involved taking a live chicken, cutting it in half and applying it to the bite site with the idea it would pull the venom from the victim. Often the animals used in treatments may be snakes or parts of snakes, a practice that extends back in time to at least Hypocrites who prescribed a broth of vipers. Smearing the skin with a powder made from the dried heads and venom glands of snakes is believed by some snake charmers to rendering them immune to snake venom. Snake gall bladders, snake heads in wine, snake blood, the rattle of the rattlesnake, powdered teeth (from snakes, crocodiles, and humans!), and a variety of treatments that involved milk (including a poultice of melted cheese), were commonly believed to neutralize or remove snake venom. Fats and oils from snakes and other animals were also popular remedies.

Mud has also been proposed as a poultice for snake venom; a South Africa resident believed he could handle venomous snakes with impunity because as a child playing on the veldt, he was bitten by a puff adder. His father removed the poison glands from the snake and soaked small balls of mud in the venom. The storyteller said his father occasionally made him ingest one of the venom-laced mud balls rendering him immune to snakes.

The term “snakestones” has been applied to several different kinds of objects. Carved elongated stones with images of snakes have been used as memorials to fallen Hindu warriors. The name has also been used to describe fossil ammonites, remains of ancient mollusks with coiled shells, some of which have been carved to look like snakes. However, for our discussion snakestones are objects used to extract venom from snakebite victims and to repel venomous snakes from human and their animals.

Bezoars, were considered a type of snakestone, and were valued as snakebite remedies for many centuries. The 8th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica had a long entry for bezoars, but the article disappeared from the 9th edition, possibly because it was considered to be superstitious. Apparently, there were several kinds of bezoars, one was a concretion of hair and other undigested material found in the stomachs of ruminant animals. Lord Lytton in his Strange Story described a black bezoar used by Corfu peasants, applied to a snakebite it absorbed the toxins, falling off when saturated. Placing it in milk would release a green scum that floated on the milk’s surface and the bezoar could then be reused.

In Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Sir Emerson Tennant described serpent stones as black, highly polished and used to cure cobra bites. Crooke reported a northern Indian belief that when a goat kills and eats a snake, it ruminates and then regurgitates a mankan or bead. The bead absorbs venom when applied to snakebite and swells; the venom is removed by soaking in milk, if not placed in milk the bead fragments. Snake charmers of Padmakesharpur in the Indian state of Orissa reportedly use a snakestone obtained by killing a charal bird, and removing the stone from its head.

On the Caribbean island of Trinidad, local people use the Belgian Black Stone for snakebite, a remedy obtained from a Belgian Roman Catholic priest, who reportedly obtained the technique from a Brazilian tribe. The “stones” are made by burning deer horn or animal bone, and the remedy was presumed to work because it is extremely absorbent. Needless to say, snake stones are not considered an effective treatment for snakebites by modern medicine.

Felix Fontana was one of the first to experiment with venom and venomous snakes; he performed 6000 experiments on more than 4000 animals and used more than 3000 vipers. Fontana included experiments on the effects of electricity on venom. He wrote,

I have likewise tried electricity against the bite of the viper, and have not only founded useless, but it has even appeared to be hurtful. It is at least certain that in the animals to which I applied it, the complaint became more violent, and that they died sooner. In many, I threw sparks from the conductor, on the part bitten; and in others drew sparks from the part, keeping animals fastened to the conductor: in both ways, I found electricity more hurtful than beneficial.

Despite this early observation that the use of electricity to cure snakebite was ineffective, electricity as a snake bite treatment had a renaissance in the 1980’s, originating with a letter to the British medical journal, Lancet, by Dr. Ronald H. Guderian, a missionary doctor in Ecuador who described success in treating 41 cases of poisonous snakebite with electrical shocks from a stun gun. The bites were treated with high voltage, low current shocks lasting one to two seconds, and applied at intervals of five to ten seconds as close to the bite site as possible. However, there were questions about the identification of the snakes, were they venomous species? Follow-up studies did not support the original findings. Science is picky about the ability to duplicate results for verification, and the use of electricity to cure snakebite is not accepted today.

All of these quaint folk preventions and treatments are of course dangerous for they may encourage people to take unnecessary risks with venomous snakes and delay proper treatment should envenomation occur. So if traditional treatments are indeed ineffective, then how do snake charmers avoid the effects of venom? And, how have these folk remedies, which do not work, remain viable solutions in the minds of hundreds of millions of people the world over for centuries?

The answers to these questions are not immediately obvious. First, not all snakes have the ability to harm humans and distinguishing dangerous species from non-dangerous species is not always easy. Secondly, not all venomous snakes are lethal to humans. Third, during a defensive bite a venomous snake may not inject a lethal dose of venom; in fact, it may not inject any venom at all. These bites are referred to as dry bites or cold bites and they occur quite frequently, possibly 30-50% of the time. A shaman, priest, or medicine man attempting to deal with a snake bite has a very good chance of succeeding if the snake was not dangerous to humans, or a venomous snake delivered a dry bite or a sub-lethal dose of venom.

Snake charmers may escape the consequences of snake venom by fixing the snake so that human handlers cannot be envenomated, techniques involve sewing the snake’s mouth shut; pulling or cutting out the fangs, or plugging the snake’s fangs with wax, or some other material. In a study of West African snakes, French herpetologist André Villiers noted snake charmers rubbing plant material over the snake’s body and placing the herbs in the snake’s mouth that resulted in paralysis of the jaw muscles and inflammation of the venom gland. Such materials could incapacitate the snake and make it safe for handling. The Mintons’ report North African snake charmers stretching cobras out, pressing them to ground and rapping the snake on the head. The snake became stiff and remained in that state for minutes. They suggest that this behavior may account for the Biblical stories of staffs turning into snakes.

However, not all snake charmers engage in these practices. Some use techniques that are not harmful to the snake, and these methods arise from an understanding of snake behavior and the willingness of the handler to assume the risk of a potentially lethal bite. Assuming the risk of a bite is often accompanied by a belief that the snake handler is immune to the venom.

Snake charmers often work by simply anticipating normal snake behavior, and Vincent Richards described the most skilled snake charmers as working with cobras on a daily basis, habituating them to handling and being able to keep the snake slightly off balance while holding the snake’s attention with a waving hand and an occasional smack on the back of the head.

Christian snake-handling cults of Appalachia have an occasional snake handler bitten, envenomated, and die, despite their belief that divine provenance will protect them if they truly believe. A death simply means the person’s faith was not deep enough.

The Pakokku snake clan of Burma mixes snake venom and tattoo ink in a weekly inoculation. Cobra venom is used on the upper body, viper venom on the lower extremities, and the venom is collected from snakes they encounter in their village. This may, in fact, protect the villagers from venomous snakes in their immediate neighborhood. Yet, there is little, or no, scientific evidence to support the idea that a human can be made immune to all snake venoms from all snake species.

In 1885 Henry C. Yarrow, then Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles at the United States National Museum, chose a rattlesnake from the Hopi kiva, examined the mouth and fangs and found them to be unaltered prior to the ceremony, later he obtained two snakes and sent them to physician and venom researcher Silas Weir Mitchell in Philadelphia for examination. Mitchell had been studying rattlesnake venom, and his examination found the snakes healthy and capable of delivering venom. However, University of Tucson herpetologist, Charles Bogert observed the Hopi release the snakes immediately after the ceremony. He then recaptured a specimen, bagged it and carried it in the crown of his hat to avoid altering the Hopi to the fact that he had stolen one of their messengers. Bogert examined the snake’s mouth and found the fangs had been removed. He sent the animal to rattlesnake expert Lawrence Klauber for further inspection; Klauber’s dissection discovered the fangs and the replacement fangs had been removed using a very skillful surgical procedure. Furthermore, Bogert reported that cobras handled in India and night adders used by African snake charmers also had their fangs removed. Clearly, these animals had been rendered harmless by surgery, and with the fangs and replacement fangs remove they were unable to deliver venom during a bite.

The Snake Charming School Murders

Homicide by poison was a thriving business in Europe and Asia prior to the end of the 19th century, a business that involved the Pysili and the Marci discussed earlier. Indian bazaars were particularly well known as markets for a wide assortment of plant materials and minerals that could be used to eliminate an annoying relative or competitor.

Norman Cheevers suggested homicide by snakebite has been a common crime since ancient times and he found Hindu and Islamic laws that support the hypothesis. Halhed’s Code of Gentoo Laws, p 262–263, states “If a man, by violence, throws into another person’s house a snake or any other animal of that kind, whose bite or sting is mortal, this is Shahesh, i.e., Violence. The magistrate shall fine him five hundred puns of cowries, and make him throw away the snake with his own hand.” Cheevers, also found an Islamic law that stated, “If a person brings another into his house, and puts a wild beast into the room with him and shut the door upon them, and the beast kill the man, neither kisas nor diyat is incurred; and it is the same if a Snake or Scorpion be put into the house with a man, or if they were there before, and sting him to death. But if the suffer be a child, the price of blood is payable.” The fact that these laws were on the books suggest these crimes were a problem.

Cheevers, a Surgeon-Major in His Majesties Bengal Army, a professor of Medicine, and president of the Bengal Social Science Association; also authored the Manual of Medical Jurisprudence for India published in 1853. In the 1870 revision Cheevers documents an incident in which three men attending snake charmer lessons were killed by bites from a krait induced by their tutors, Poonai Fatmah and Joomu Fatmah. The motive is unclear, but it seems likely the tutors wanted to demonstrate their powers as gooroos and bring snakebite victims back to life as a lesson for the other students.

On Sunday October 11th, 1868 at Hurdah, Zillah Purneah, in Bengal ten men were receiving snake charming lessons from the Fatmahs. One man, Titroo was told to extend his right hand onto the ground near a large krait. Titroo expressed fear at being bitten, but the Fatmahs bullied him, saying “Why are you afraid? If the snake does bite, we will charm you, and recover you.” The krait was made to crawl toward Titroo’s hand and when it did not bite him, Poonai Fatmah struck the snake with a cane. Titroo was bitten on his fore-finger. The event was repeated with two more men, Menghon and Jikree. A fourth man, Etwarree was also forced to allow the snake to bite him on the wrist, but he survived to testify against the Fatmahs. Etwarree attributed his survival to the fact that snake may have been out of venom or dead when it bit him. The Fatmahs were sentenced to 5 years in prison.

Snake Charmers and Science

Science, like magic and religion, is a human attempt to control nature, and it is the only successful approach of the three. Science uses its methodology to develop an understanding of the natural world based on rational thought as opposed to supernatural forces, folklore, or sacred texts. And, only science can provide insight into how snake charmers avoid venom and control snake behavior.

Cobras are the ultimate snakes for the charmer. Their behavior of rearing up into a defensive position, expanding a spectacular hood, striking downward from the reared posture, their ability to be easily distracted, their tendency to crawl away from a disturbance in a relatively straight line, and their general timid nature make cobras relatively easy to manipulate. Additionally, the cobra’s widespread reputation for being aggressive, its highly toxic venom, its spectacular hooded posture making it immediately recognizable, and its ability to cause human death serve to amplify the charmer’s performance in the mind of the viewer. Snake charmers, like magicians, depended heavily on the expectations and preconceived notions of the audience.

Spaeth tells a story of a Hindu snake charmer who erred with an 11-foot hamadryad or king cobra. The bitten man refused medical assistance and antivenin, and died within six hours. She writes, “His death proved, in any case, that science is the only successful snake charmer.” I agree. Science is the only consistently successful method that humankind has found to deal with snakes and nature; our other options, namely magic and religion, have failed. Science remains human’s best hope of discovering and understanding the nature of the universe and snakes.

Purpose of the Book

This is a story created from personal experiences as well as those of other herpetologists, a story that will arouse, and absorb the reader into the world of snakes. The book’s focus will be on the role of snakes in the environment and their evolutionary biology with an emphasis on research done since 2000 and how it has altered our view of snakes. Included are some traditional historical references to place current knowledge in perspective. While this is an attempt to summarize current research, the research is continually changing and by the time this goes to press there will undoubtedly be new information, hypotheses, and twists to some of the stories discussed here. Unfortunately, not all of the research could be included. Inspiration for this work comes from Sherman and Madge Minton’s 1980 Venomous Reptiles, and Harry Greene’s 1997 Snakes, The Evolution Mystery in Nature.

Chapters 2 and 3 discuss what we know about the origins and diversification of lizards into snakes. Chapter 4 is a discussion of the confusion created by the idea that some snakes are venomous while others are not and how this confusion lead to the deaths of some well-known 20th century herpetologists. Chapter 5 and 6 focus on the venom apparatus and venom; who gets bitten by snakes, the discovery of antivenin. The extreme adaptations snakes have to feeding and avoiding predation are topics for Chapters 7 and 8. Biogeography is discussed in chapter 9, with an emphasis on island snakes. Chapters 10–13 examine snake adaptations to aquatic, arboreal, and fossorial environments. Chapter 14 looks at the value of snake and why snakes are both aesthetically and economically important.

Comments

Post a Comment